Introduction to Quantum Computers

Introduction

We will look at a little bit of the history of quantum computers. First, we will examine the physics that inspired the creation of quantum computers. Next, we will look at three famous algorithms that show the potential of quantum computers. Finally, we will take a peek at current hardware support.

Waves and Particles

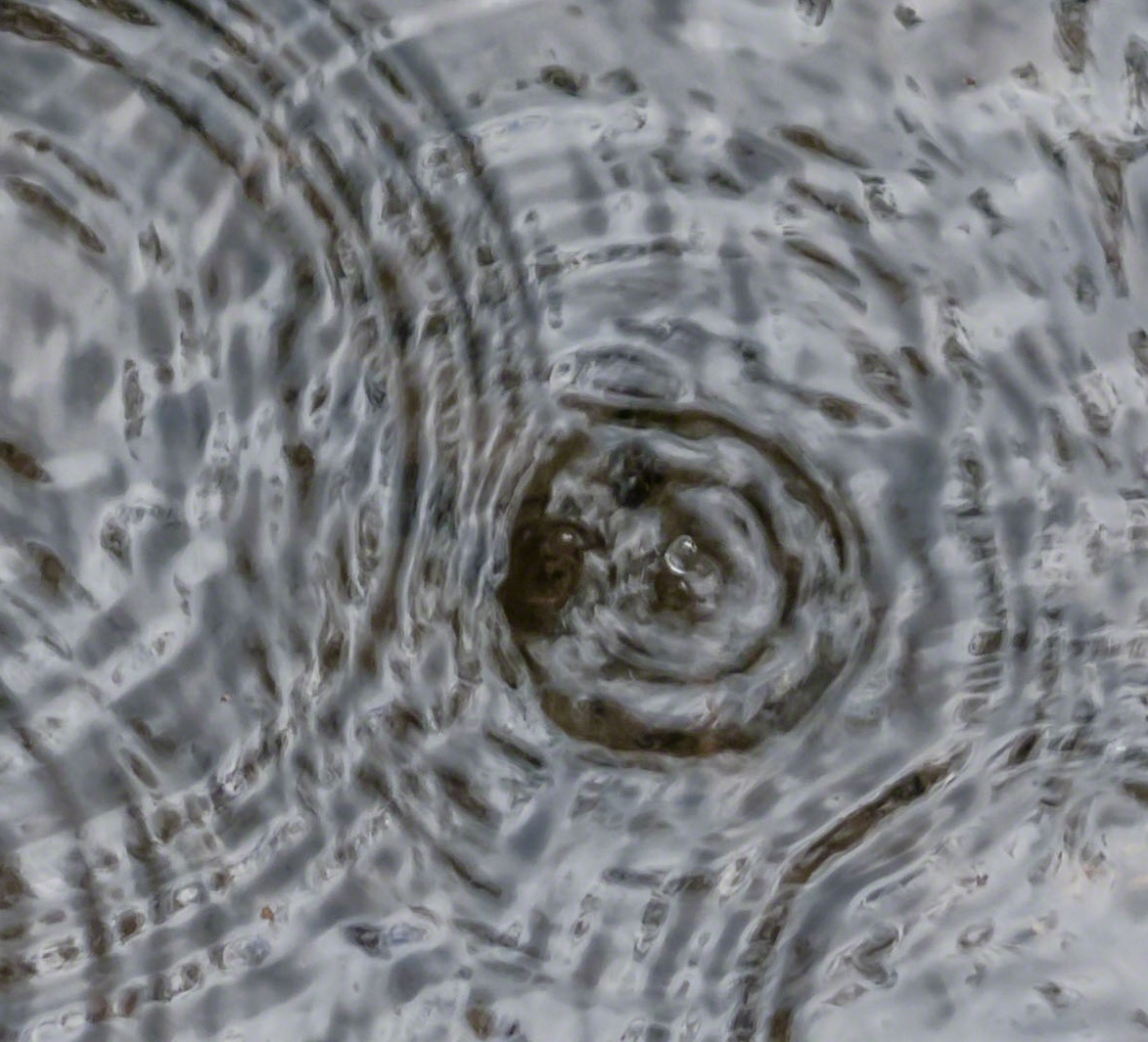

Ripples of Water by Kristen / Adobe Stock Photo

Ripples of Water by Kristen / Adobe Stock Photo

When you drop something in water, it causes ripples to form. These ripples are waves. A wave is a disturbance in the water that propagates outward from the source. If we drop a stone in the water, the waves of water ripple out from the source. The above image has many waves rippling out. Look at the points where the waves overlap. Sometimes the waves case interference with each other. In constructive interference, the waves overlap and combine to make an even stronger wave. In destructive interference, the waves overlap and weaken each other. The image is zoomed in below to show interference patterns.

Zoom in on Ripples of Water by Kristen / Adobe Stock Photo

Zoom in on Ripples of Water by Kristen / Adobe Stock Photo

We have known that water ripples like this for as long as we have interacted with water. Our story gets exciting when scientists discovered other things could causes similar ripples. This basic idea will eventually lead to the invention of Quantum Computers.

For a very long time, people believed that light would move like a particle. To imagine a particle, think about shooting a bullet out of a gun. The bullet is a particle. It will move in a straight line unless something effects it. Gravity might pull the bullet down or a target will change it’s path. The bullet wants to go in a straight line as long as it has the energy to do so.

Shooting at a Target by Parathaan / Adobe Stock Photo

Shooting at a Target by Parathaan / Adobe Stock Photo

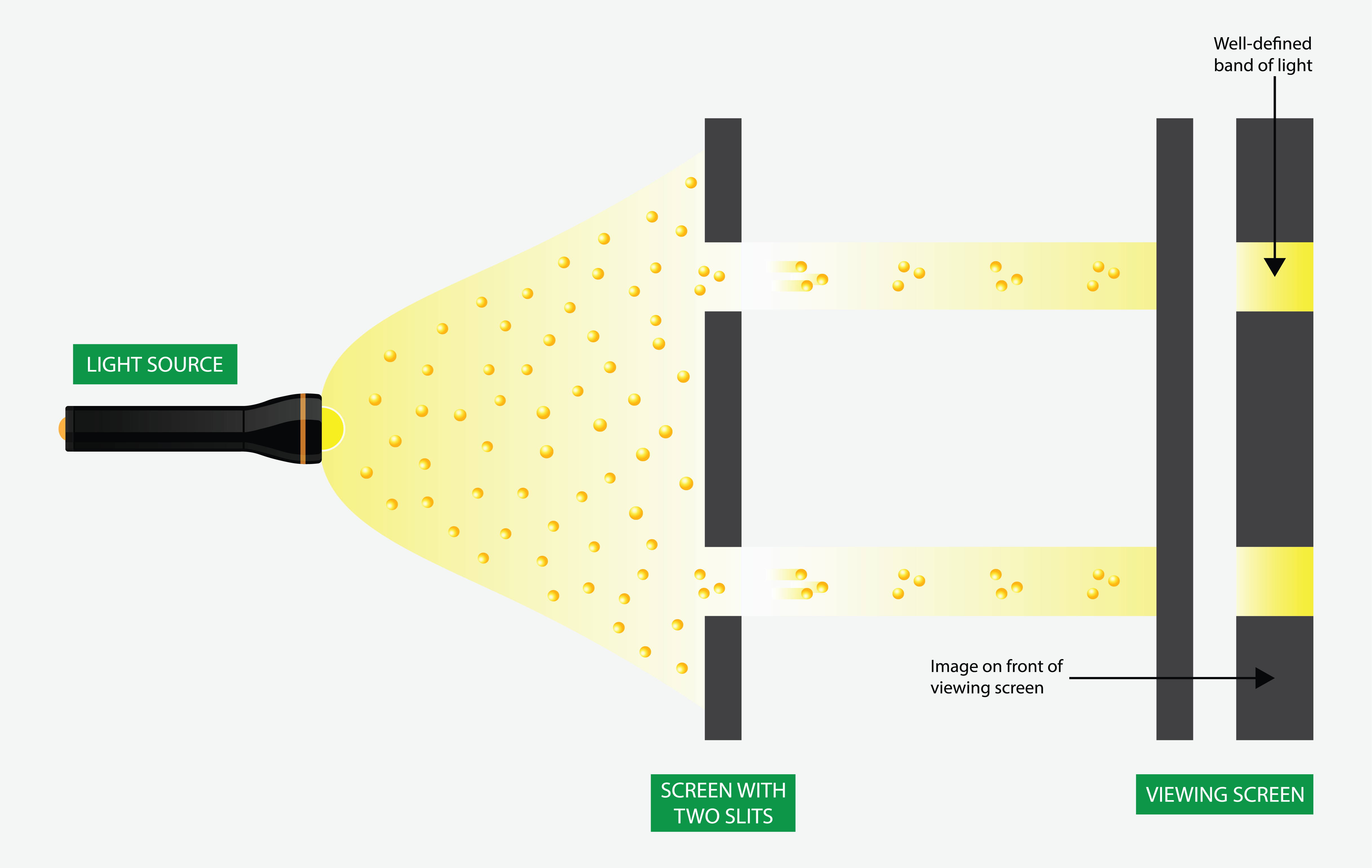

Imagine we put a wall with two slits in it between the shooter and the targets. The bullets can only reach some areas of the targets. The bullets have to move in a straight line. There are only so many places they can go. If light moves like a particle, it should act just like bullets from a gun. If we put a wall with slits between a light source and a wall, where will the light go? We expect that there are only some places the light can reach.

Particle Slit Experiment by Watthana Tirahimonch / Adobe Stock Photo

Particle Slit Experiment by Watthana Tirahimonch / Adobe Stock Photo

In 1801, Thomas Young showed this was not the case! In 1804, Thomas Young published a seminal work The Bakerian Lecture. Experiments and calculations relative to physical optics describing the details of this discovery.

Portrait of Thomas Young by Henry Perronet Briggs, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of Thomas Young by Henry Perronet Briggs, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

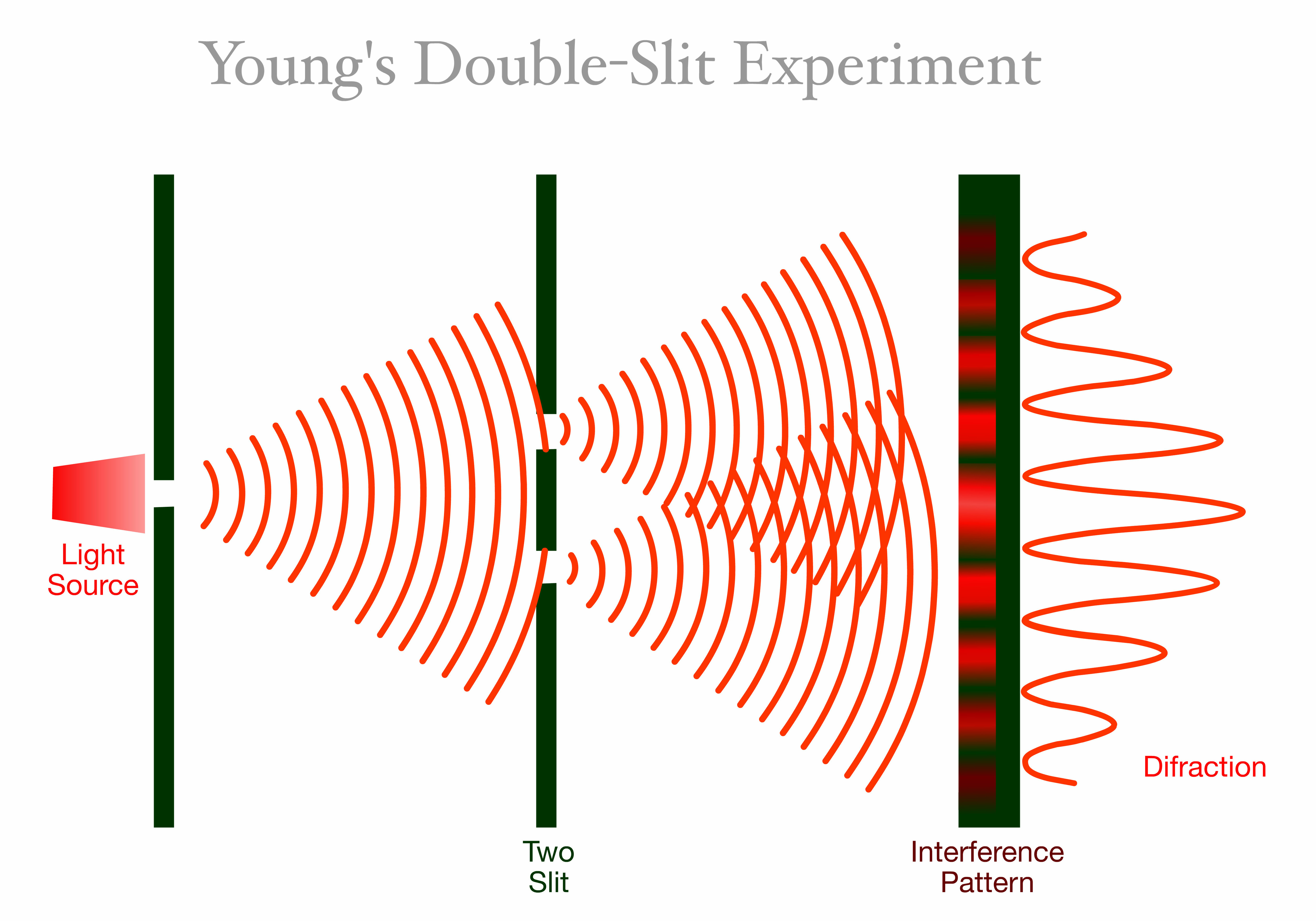

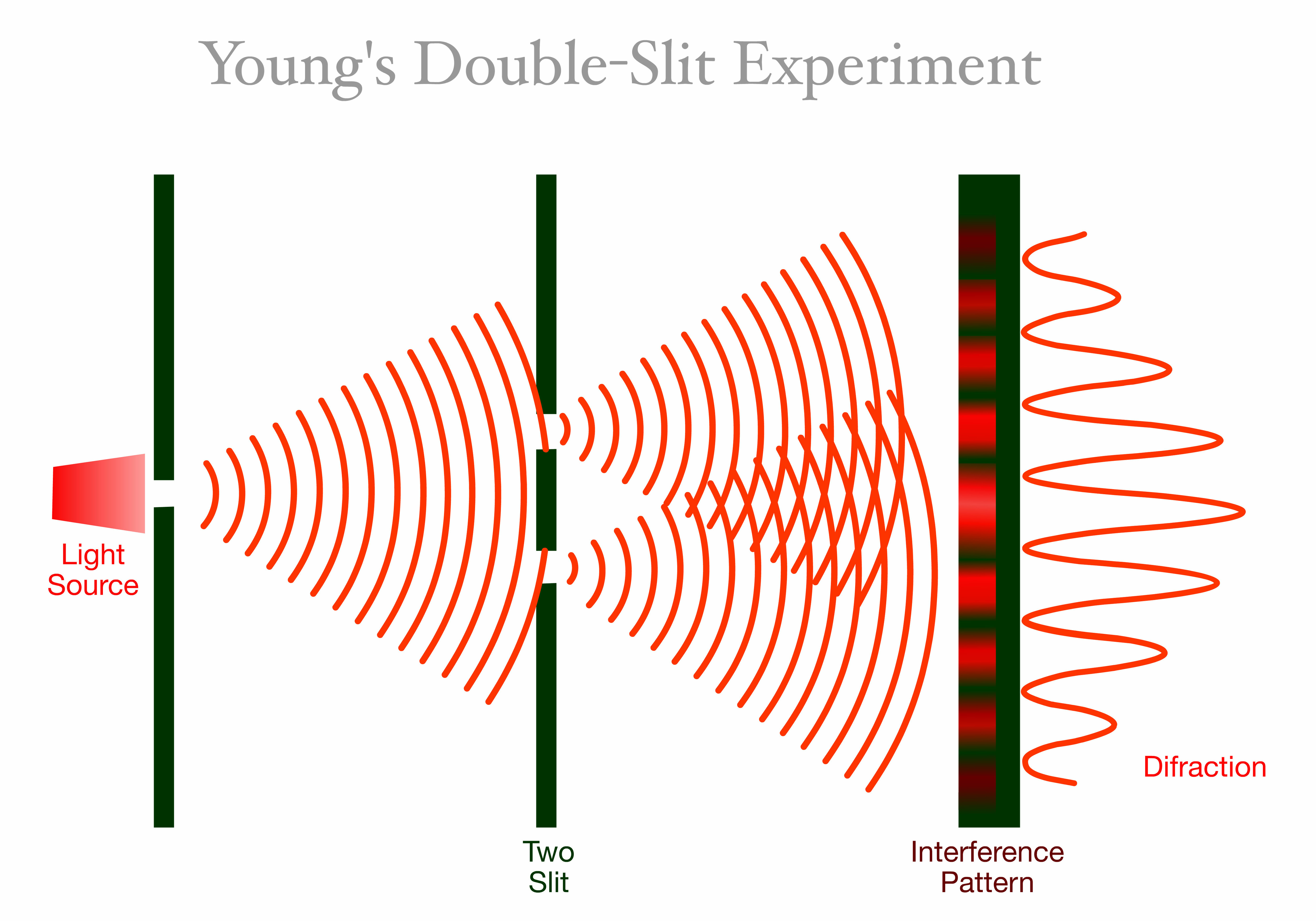

Thomas Young showed that light behaved like waves of water, not like particles. When a light was projected through two slits, a wave interference pattern is created. Light was rippling like a wave!

Thomas Young’s Experiment by LuckySoul / Adobe Stock Photo

Thomas Young’s Experiment by LuckySoul / Adobe Stock Photo

You can replicate this experiment whenever you want. All you need it light, a wall, and something with two slits in it. You can also replicate it with water.

In 1804, scientists proved that light acts like a wave. This opened a whole new area of study. What is the light rippling in? How can light cause interference? What about the fact that light seemed like a particle in other situations? Basically, “what is light?”

It took many years of work to start getting answers to these questions. Some questions still don’t have answers.

Quantum Mechanics

The next big set of breakthroughs begin in 1920s. This is when the math behind Quantum Mechanics begins to solidify. Scientists learn that all quantum particles act like light. They seem like waves sometimes and particles sometimes.

Many physicists did amazing work during this time period. We will focus on Erwin Schrodinger. His discoveries will tie in closely with Quantum Computers.

Erwin Schrodinger in 1933 Nobel foundation, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Let us briefly return to our double slit experiment. What if you only send one single photon of light at a time out of the light? Thomas Young did not have the technology to send one single photon out of a light source. We can do this with modern technology. Surely, the wave interference pattern cannot still happen. How would one photon interfere? There would be nothing to interfere with!

Thomas Young’s Experiment by LuckySoul / Adobe Stock Photo

Thomas Young’s Experiment by LuckySoul / Adobe Stock Photo

The interference pattern will still happen even if you shot the photons out one at a time. Even if you make sure the first photon hit the target before the second one is released. The photons have to be causing interference patterns with something.

In 1926, Erwin Schrodinger published a paper Quantization as an Eigenvalue Problem which presents the Schrodinger Equation. It is not directly used in the programming of quantum computers, but it is cool. I have presented it below.

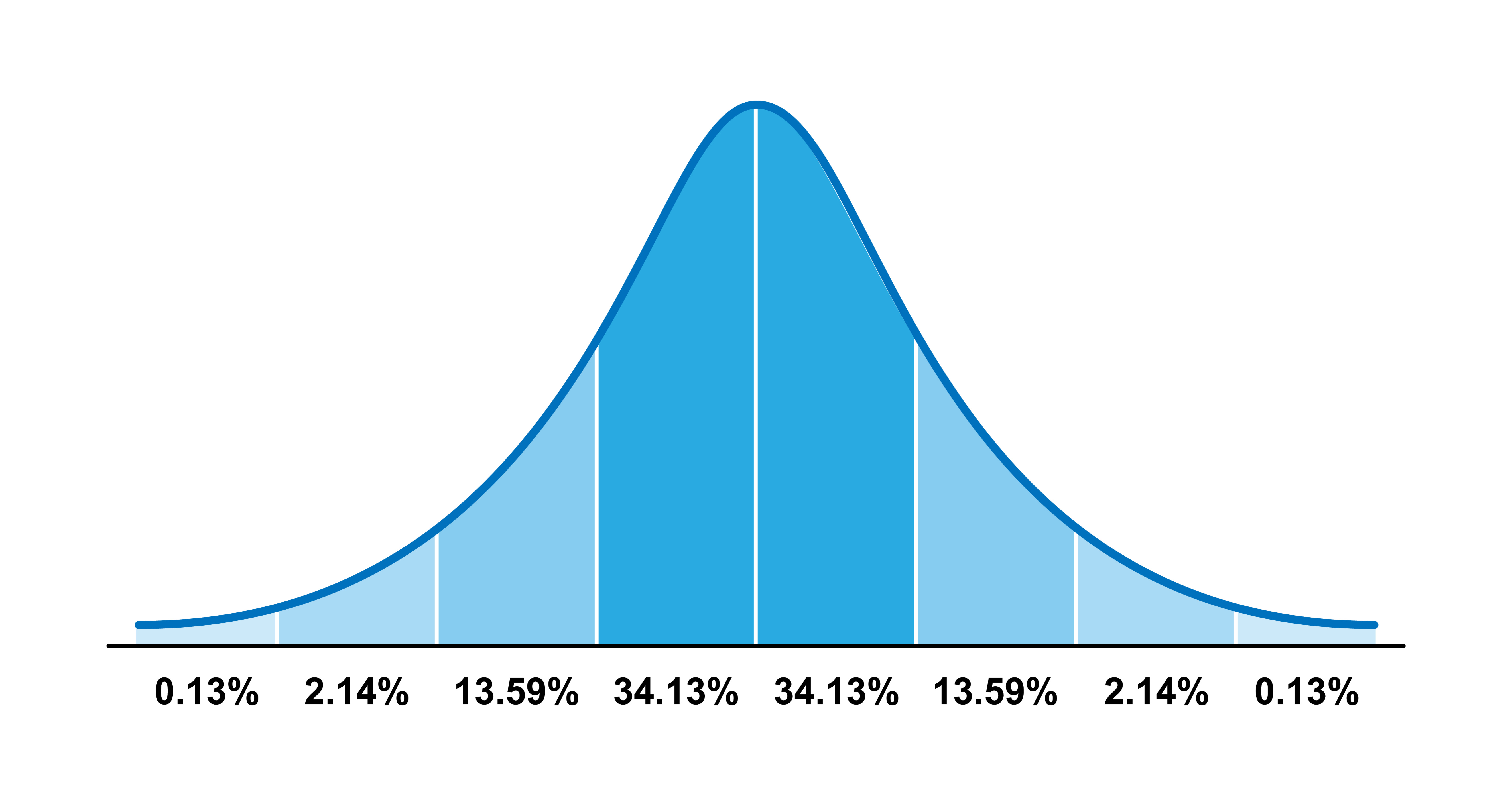

\[i\hbar\frac{\partial}{\partial t} \Psi(x,t) = \left [ - \frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\frac{\partial^2}{\partial x^2} + V(x,t)\right ] \Psi(x,t).\]Erwin Schrodinger’s results can be interpreted as a probability wave. Our single photon of light has a probability of being in different places at the same time. If the photon’s position was defined by the plot below, the photon would have a 68.26% chance of being in the deep blue middle of the plot. It would have a 0.13% chance of being in the far right side of the plot. Every position is somewhere the photon might be with a certain probability.

Probability Distribution by Lifeking / Adobe Stock Photo

Probability Distribution by Lifeking / Adobe Stock Photo

When we shot a single photon through the two split experiment, what is it interfering with? The answer is itself! The probability waves from the single photon are interfering with each other. This is increasing the probability of the photon being in some places and decreasing the probability it is in other places. It is almost like the photon when through both slits at the same time somehow.

This leads to a concept called superposition. It is possible for a quantum particle to be in two places at once. When the particle interacts with something measuring it’s position, we find out where it is. As long as its position is a mystery, it is in two places at once.

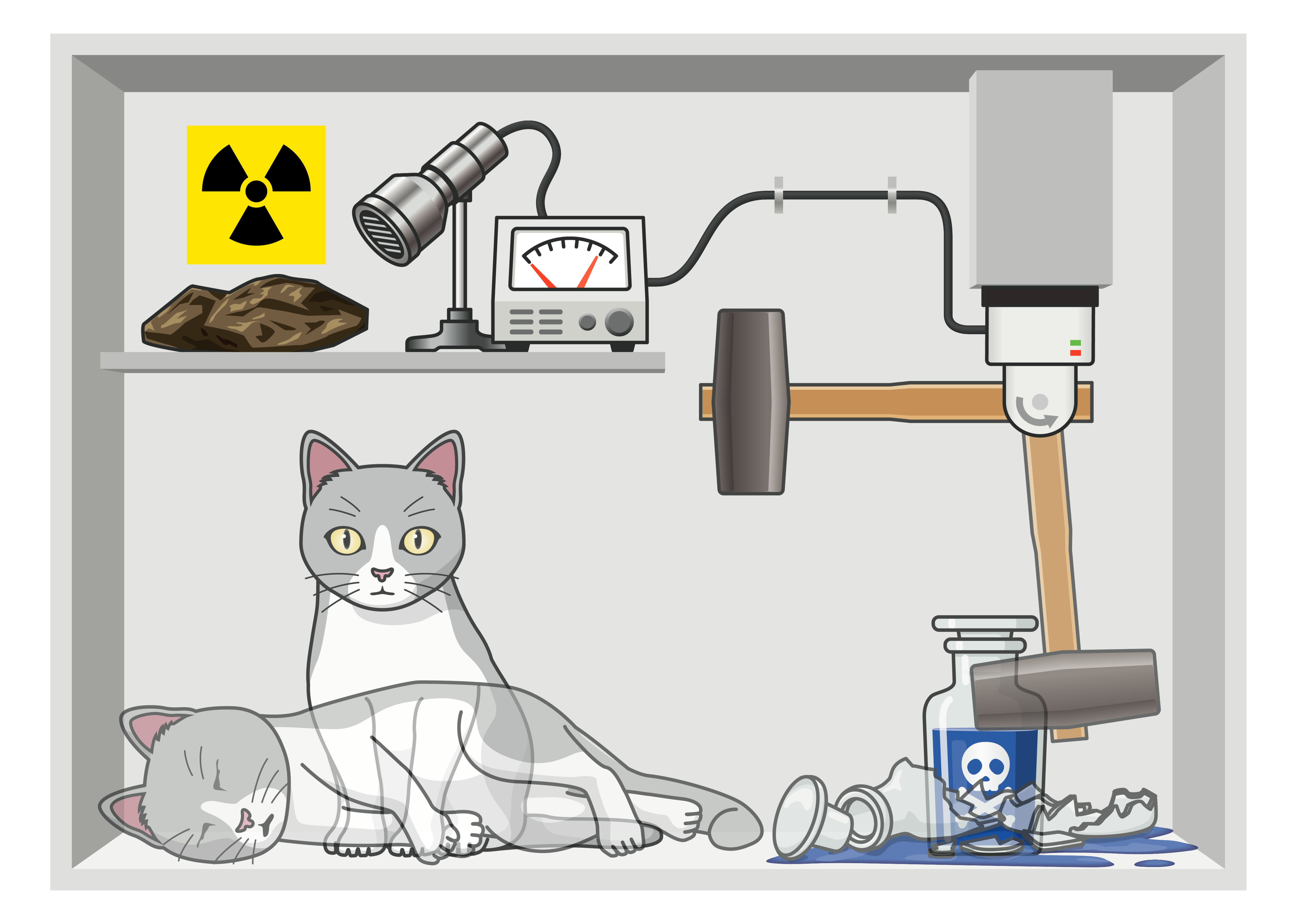

This leads to a famous thought experiment called Schrodinger’s Cat.

Schrodinger’s Cat by Atarashi YO / Adobe Stock Photo

Schrodinger’s Cat by Atarashi YO / Adobe Stock Photo

This experiment helps people imagine how superposition works. We start with a closed box. The box contains a cat. It also contains a radioactive material. If the radioactive material releases a quantum particle it will cause a toxin to be released. The cat will be killed. The radioactive material will release a particle 50% of the time. The other 50% of the time, it leaves the cat alive. Since the box is closed, we do not know the position of the quantum particle. That means the cat is alive 50% of the time and dead 50% of the time. Until we open the box, the cat is both alive and dead at the same time. It is in a superposition state.

This is nonsense for cats, but it does happen for quantum particles like photons or electrons. They really are both alive and dead at the same time, until we look at them and find out.

We now have the two tools that will explain why quantum computers can be so powerful. We have seen wave interference can increase or decrease the probability of certain events taking place. We have also seen superposition allows a quantum particle to be in two places at once.

It is hard to imagine what superposition really means. Some scientists will just take the position that it doesn’t matter because it works. The math makes sense, don’t worry about the rest. One possible interpretation, is called the Many-Worlds Interpretation. This was proposed by Hugh Everett in 1957.

The Many-Worlds Interpretation proposes that each different position the particle could be in is actually a different universe in the multiverse. The different universe are interacting with each other. When we look at the position of the particle, we find out which universe we are in. There is a universe where the cat is alive and one were it is dead. We don’t know which one we are in unless we open the box.

One way to imagine this in our normal world is with radio waves. A radio can be tuned to many frequencies. There are many radio stations (universes) in the room with you right now. You can tune a radio and target one of them. The radio stations can interfere with each other, even though you can only ever focus in on one (Kaku, 2023).

Quantum Computers

In 1982, a physicist, Richard Feynman, published a paper Simulating Physics with Computers. This paper is the first to propose that a computer could be build using Quantum Mechanics. Richard Feynman worked on the Manhattan Project along with Robert Oppenheimer. Richard Feynman spent much of his like doing quantum physics research and won the Nobel Prize in 1965 for his physics work. Sadly he would pass away in 1988, before the hardware to create Quantum Computers could be created (Krauss).

Two things needed to be created before anyone could take Richard Feynman’s idea and use it. Quantum algorithms needed to be created that could do something classic computers could not do. Quantum hardware needed to be build that would allow us to make use of quantum mechanics to do computations. We needed a reason to build a quantum computer (algorithms) and the technology to do it (hardware).

Quantum Algorithms

Even without physical hardware, scientists can develop algorithms. The algorithms can be proven either on paper (with math) or through simulations on classic computers. These proofs show that the algorithms would work. They are just so slow that you could never use them in practice without quantum hardware.

You could easily sort 10 books in alphabetical order to prove it can be done. If you were asked to sort every book in Drexel University’s library, it would take a long time. It is not that you don’t know how, it is just that by yourself the method takes too long. You can think of research on quantum algorithms like this. People showed the ideas worked at a small scale, then threw up their hands. They couldn’t use their ideas for real problems without quantum hardware. The methods worked but took too long to do any other way.

Deutsch-Jozsa Algorithm

In 1992, David Deutsch and Richard Jozsa published a paper titled Rapid Solution of Problems by Quantum Computation. The problem they solved has no practical use. It does show that a quantum computer can potentially do something no classical computer would ever be able to do.

Imagine your teacher gives your class an extra credit question on a test.

Guess a number between 1 and 100?

Your teacher gives you the following information about the extra credit question. They are going to grade the question using one of the following three options.

- Every answer will get extra credit points.

- No answer will get extra credit points.

- They have picked exactly 50 numbers that will get extra credit points and 50 numbers that will not get extra credit.

You want to figure out what the teacher did by comparing your scores with the other students in your class.

A classic computer has the same problem you do with this question. To figure out which statement about the extra credit is true, you might need to verify 51 grades. In the best case, you find two students with different answers. One that got the extra credit points and one did not. You figured out the teacher used the 50/50 split method of grading.

In the worst case, you have 50 students in the class with you. Every one guessed a different number. You all got extra credit points. You can eliminate the option where no one gets extra credit. You cannot determine if the teacher actually gave everyone extra credit or the class just got lucky and guessed the 50 correct numbers. You might need a class of 51 students to all guess different numbers. Only then can you be certain what the teacher did.

Mathematically, we say that for a range of $x$ numbers we need to test at least $\lfloor \frac{x}{2} \rfloor + 1$ numbers. You need to have students guess one more than half the possible answers to figure out what your teacher did.

Deutsch-Jozsa showed that a quantum computer can find out the answer in only two experiments. It doesn’t even matter how many options are available to guess. It always takes exactly two experiments. You just need enough hardware to support all the different possible guesses, but the algorithm only needs two experiments.

On a quantum computer, we answer the question with every different number using superposition. A different version of one student takes the test giving different answers in multiple universes all at the same time. Then we use interference. We create a system where correct answers and incorrect guesses will interfere will each other. In one situation, all the answers get extra credit. In one situation, all the answers get no extra credit. In the final situation, exactly half get credit and half don’t. Since these are opposites they can interfere with each other.

The quantum computer can look at the results. It can tell us if the interference happened or not. If it did, we know the answer is 50/50 split. If not, we know every guess got the same score. Then we just need 1 graded test to know if everyone got extra credit or not.

This situation doesn’t happen much in real life. This makes Deutsch-Jozsa’a algorithm worthless for most real world problems. The important thing about the algorithm is that it proposed something that no classical computer could ever do. A classical computer can solve the problem, but never as fast. It has to try one more than half of the possible answers. This proved Quantum Supremacy. Quantum Supremacy means a quantum computer can do things that are impossible for classical computers. This algorithm inspired many more practical algorithms to be created. It sparked a fire by showing that new algorithms could be created.

Shor’s Algorithm

Peter Shor published two papers in 1994 and 1997 that showed how Quantum Computers can be used to find prime factors. Factoring numbers is probably something you had to do in grade school. For example, 78 factors into $2 * 3 * 13$. Those are the prime numbers that can be multiplied to get 78. You probably did this by trying division by different prime numbers. Computers can do the same thing, but it takes a long time for large numbers.

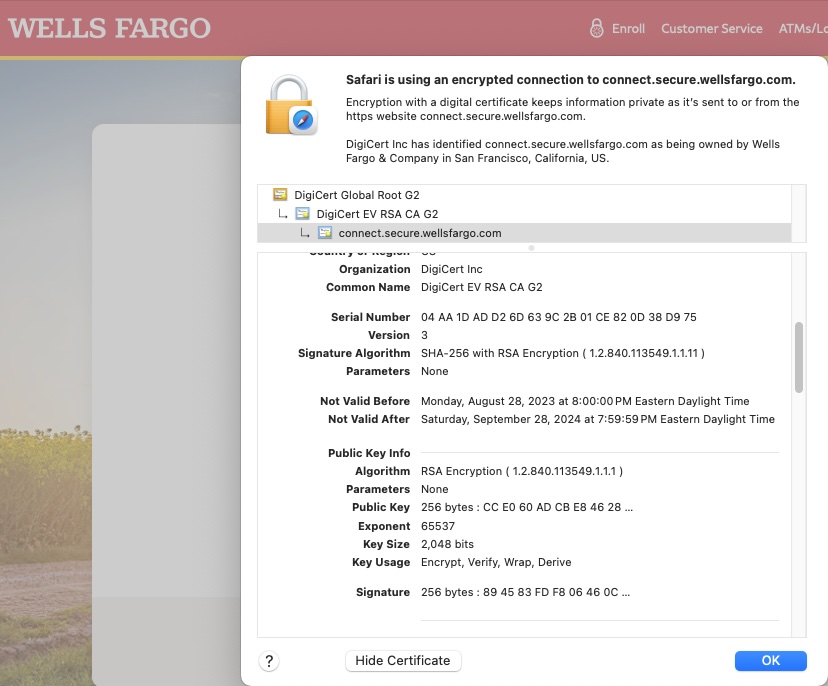

Large numbers are used in many security fields. Below is a screen capture of Wells Fargo’s website. It uses encryption to make sure your password is not stolen when sent over the internet. There is a value called the Public Key posted on this page.

Wells Fargo Screenshot

Wells Fargo Screenshot

The Public Key is very long. It is shown below in its entirety. This is just one single very large number.

10603413510384702862118306716652257153163688936561632130257939037553672147758177617880613304986755994961515902822903200144400551854910692945746237321689357454777281577572378207766943457653302788315618689949273535756943421464751936585915264526895053748691535408954598348134064989106062578643071441795519617540785619512522489206605480521965738714091009672274739683797350758151705533988194065604470809177616861908364634468137219863007291012107945624422131624651660194763147525697121596834023861285244430760421108585033191809266293615050666236004357690389850123292725070520295693549852311013325258354673334096140053353325

If you could factor it, you could find out the passwords of all the users who logged into the website. The problem is factoring it the old fashion way takes too long. If you used the best super computer on the planet, the sun would become a red giant before you found out the factors. Even if you could somehow use every computer on the planet, you would not live long enough to get an answer. Wells Fargo changes the number once in a while, so no one will ever have time to factor it. There are even stronger methods where all the computer power on the planet could not factor the number before the heat death of the universe. We call these methods secure, because we don’t care if someone hacks our website after the heat death of the universe.

Shor’s Algorithm could factor that number in a matter of hours (Gidney). Shor’s Algorithm uses a process called phase estimation to try different values in superposition then try to estimate the correct one. We don’t have anywhere near the hardware needed yet, but researchers are building better hardware every day.

This algorithm has been critical for testing the functionality of real world quantum computers. In 2001, IBM ran the first ever demonstration of Shor’s algorithm by factoring 15 into 5 and 3 on a real Quantum Computer (Vandersypen). In 2012, the number 21 was factored into 3 and 7 (Martin-Lopez). In 2019, an attempt was made to use one of IBM’s quantum computers to factor 35 into 5 and 7 (Amico). This attempt failed due to the amount of error in the quantum hardware. The algorithm was theoretically correct and verified, but the hardware just made too many errors. A paper published in 2023 showed that currently available quantum hardware makes too many mistakes to factor larger numbers (Cai). This doesn’t mean it is impossible, it just means we need hardware improvements to make Shor’s Algorithm useful for realistic numbers.

Grover’s Algorithm

In 1996, Lov Grover created a Quantum Search Algorithm. This algorithm finds something faster than any classical computer could. It searches for an input that causes something to happen in a program. A real world metaphore is a keypad lock.

Keypad Lock by Priscilla Pasos/Wirestock Creators / Adobe Stock Photo

Keypad Lock by Priscilla Pasos/Wirestock Creators / Adobe Stock Photo

You know the keypad has a 4 digit code. You don’t know what it is. You can guess all possible combinations and you will eventually find the right one. This keypad has 10 digits. If we know it has 4 digits in the code, that means it has 10,000 possible codes. You could try them all, but it will take a very long time.

Grover’s Algorithm allows a Quantum Computer to try all the codes at the same time. Imagine a different parallel universe version of you typing each possible password. Grover’s Algorithm then uses a process called amplification to increase the probability you are in the universe where you type in the correct codes. This allows a Quantum Computer to find the secret code faster than any classic computer (or person) could ever do. It cuts the number of values that need to be searched by a square root. The $\sqrt{10,000}=100$, this is a significant improvement. It is not instant, but it does reduce the amount of work needed. Instead of testing 10,000 different numbers, we only need to test 100 to find the right answer.

Quantum Hardware

Quantum algorithms have been progressing since the idea was first proposed in 1982. Hardware has also been moving forward. Hardware progress started much slower, but has been recently progressing rapidly. Algorithms can be imagined and studied in theory, but hardware needs to be built and tested.

The fundamental piece of a classic computer is the bit. A bit is a physical thing, an electrical charge on a wire. The charge can either be high or low. We call these 0 and 1. At the lowest level, everything your computer does is about changing the values of these wires between high and low. All computation is built up from this physical system.

A Quantum computer uses a qubit. This is also physical thing, but at the quantum scale. Something like a single photon, electron, or atom. The qubit must be a quantum object so that it will follow the rules of Quantum Mechanics. A qubit also has a 0 or 1 value. It is a quantum object. That means it can be in superposition and be both 0 and 1 at the same time with different probabilities. qubits can also interfere with their own probability waves or the waves of other qubits like the double-slit experiment showed.

There are three big measures of how quantum hardware is developing. One is the number of qubits the hardware can work with. More qubits mean more complicated algorithms can be run. The second measure is error. How often does a value get misread or changed by accident. If you set a value to be 1 and there is a 0.05% chance it will actually be set to 0, this is an error. Any error will cause a bad result. The final big measurement is length of time qubits can be in superposition and interact with each other. This is called quantum entanglement. It is a situation where a collection of quantum particles are all in superposition and interacting with one another. If would be great to have 1,000 qubits, but if none of them can entangle we cannot run any algorithms. Longer entanglement times mean complicated calculations can be done. Imagine if your smartphone could only be used to 10 seconds at a time. That would limit how much you could do with it.

We need to be able to do all three of these things well. Improvements are being made on all fronts right now. Different companies are trying to solve the problem in different ways.

IBM

IBM is one of the leaders in Quantum Computing hardware. They have made some of their computers open to the public. You can even run a program yourself using their cloud based systems. You normally have to wait a day or two to get results, so it is not practical. You can do it!

IBM has been pushing for systems with a large numbers of qubits. Their systems are based on superconducting circuits which are easier to manufacture than some other methods (Steffen). Their systems have a higher error rate than some others, but many qubits. In 2022, IBM completed work on a 400 Qubits system and in 2023 announced a 1,000 qubit system (Castelvecchi).

In June 2023, IBM announced that it had reached quantum utility (Kim). This means IBM successfully ran algorithms faster and more accurately than a classical computer could. They showed that the advantages imagined by researched could actually be achieved in the real world.

By 2026, IBM is planning to have the 1,000 qubit system ready for practical use (Gambetta).

Quantinuum

Quantinumm is another quantum company. They are making progress on many areas, but have fewer qubits than IBM. Dr. Mark Jackson dropped by Drexel University and gave a presentation about their work. You can watch the talk at https://1513041.mediaspace.kaltura.com/media/Introduction+to+Quantinuum+at+Drexel+CCI/1_uh2zfl0o.

Quantinuum has been focused on lower error rates. They have made significant progress on fault-tolerance (Burton). Quantinuum’s premier system has 56 qubits, but a clever solution to engagement that requires far less connections (DeCross). You can see a video or read more at https://www.quantinuum.com/news/quantinuums-h-series-hits-56-physical-qubits-that-are-all-to-all-connected-and-departs-the-era-of-classical-simulation. They have already shown practical applications in work they have done with JP Morgan Chase.

Quantinuum is already using their system for work in the financial sector, chemistry simulation, and security. They are expecting to have more results that beat anything a classical computer can do in the coming years.

University of Pennsylvania

Right down the road from Drexel University, the University of Pennsylvania is also working on a quantum computer. The Penn Quantum Hardware Lab is building it’s own quantum computer. Their system uses single electrons as the qubit. They are working hard to lower error rates on a small qubit system. With only a two qubit system they can get 99% accuracy (Mills).

Moving single electrons around a computer is still a new area of research. The research hardware needs to be cooled to under a degree above absolute zero. It moves single electrons through the system and uses extremely fast signals to compute with these electrons as qubits. This method has a lot of potential if it can be fabricated at larger scales.

The author at the Penn Quantum Hardware Lab

Conclusions

In the 1800s, scientists learned that light had the properties of both a wave and a particle. It took over a hundred years before scientists like Erwin Schrodinger started to really grasp the implications and meaning behind this. In the 1980s, Richard Feynman proposed that quantum physics could be used to build quantum computers. In the early 1990, scientists started to design algorithms that could be run on quantum computers. Importantly, they showed if you could build a quantum computer it could do things no classical computer could. It wasn’t until very recently that quantum hardware reached the point were it could be used for anything useful. Even now, its uses are very limited and mostly experimental. Companies like IBM are pushing the number of qubits in quantum computers. Other researchers like those at Quantinuum and the University of Pennsylvania are chasing other problems. Both Quantinuum and IBM have successful done experiments to show quantum utility. To build practical systems, we need all the problems solved. We need good algorithms. We need enough qubits to do the job. We also need low (or nonexistent) error rates and longer entanglement times. There is still a lot to do before quantum computers are outside of research or specialty areas. The trend seems to be positive and hopefully if things continue quantum computers will be another leap forward in our technological evolution.

References

Amico, M., Saleem, Z., & Kumph, M. (2019). Experimental study of Shor’s factoring algorithm using the IBM Q Experience. Physical Review A. http://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.100.012305

Burton, Simon, Durso-Sabina, Elijah, and Brown, Natalie C.. (2024). Genons, Double Covers and Fault-tolerant Clifford Gates.

Cai, Jin-Yi (2023). “Shor’s Algorithm Does Not Factor Large Integers in the Presence of Noise”. https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.10072.

Castelvecchi, Davide. IBM releases first-ever 1,000-qubit quantum chip. Nature 624, 238 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-03854-1

Matthew DeCross, Reza Haghshenas, Minzhao Liu, Enrico Rinaldi, Johnnie Gray, Yuri Alexeev, Charles H. Baldwin, John P. Bartolotta, Matthew Bohn, Eli Chertkov, Julia Cline, Jonhas Colina, Davide DelVento, Joan M. Dreiling, Cameron Foltz, John P. Gaebler, Thomas M. Gatterman, Christopher N. Gilbreth, Joshua Giles, Dan Gresh, Alex Hall, Aaron Hankin, Azure Hansen, Nathan Hewitt, Ian Hoffman, Craig Holliman, Ross B. Hutson, Trent Jacobs, Jacob Johansen, Patricia J. Lee, Elliot Lehman, Dominic Lucchetti, Danylo Lykov, Ivaylo S. Madjarov, Brian Mathewson, Karl Mayer, Michael Mills, Pradeep Niroula, Juan M. Pino, Conrad Roman, Michael Schecter, Peter E. Siegfried, Bruce G. Tiemann, Curtis Volin, James Walker, Ruslan Shaydulin, Marco Pistoia, Steven. A. Moses, David Hayes, Brian Neyenhuis, Russell P. Stutz, & Michael Foss-Feig. (2024). The computational power of random quantum circuits in arbitrary geometries.

Deutsch David and Jozsa Richard. 1992 Rapid solution of problems by quantum computation. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A439553-558 http://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1992.0167

Everett, Hugh (1957). “Relative State Formulation of Quantum Mechanics”. Reviews of Modern Physics. 29 (3): 454-462. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.29.454

Feynman, R.P. Simulating physics with computers. Int J Theor Phys 21, 467-488 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02650179

Jay Gambetta. IBM Quantum roadmap to build quantum-centric supercomputers at IBM Quantum Computing Blog. 10 May 2022. www.ibm.com/quantum/blog/ibm-quantum-roadmap-2025.

Gidney, Craig and Ekera, Martin. 2021. How to factor 2048 bit RSA integers in 8 hours using 20 million noisy qubits. Quantum 5, 433. http://dx.doi.org/10.22331/q-2021-04-15-433

Grover, Lov K. . 1996. A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search. In Proceedings of the twenty-eighth annual ACM symposium on Theory of Computing (STOC ‘96). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 212-219. https://doi.org/10.1145/237814.237866

Kaku, M. (2024). Hyperspace: A Scientific Odyssey Through Parallel Universes, Time Warps, and the Tenth Dimension (1st ed.). Oxford University Press, Incorporated.

Kaku, M. (2023). Quantum Supremacy: How the Quantum Computer Revolution Will Change Everything (1st ed.). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

Kim, Y., Eddins, A., Anand, S. et al. Evidence for the utility of quantum computing before fault tolerance. Nature 618, 500-505 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06096-3

Krauss, L. M. (2011). Quantum man: Richard Feynman’s life in science (1st ed.). W.W. Norton.

Martin-Lopez, E., Laing, A., Lawson, T. et al. Experimental realization of Shor’s quantum factoring algorithm using qubit recycling. Nature Photon 6, 773-776 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2012.259

Mills, A., Guinn, C., Gullans, M., Sigillito, A., Feldman, M., Nielsen, E., & Petta, J. (2022). Two-qubit silicon quantum processor with operation fidelity exceeding 99%. Science Advances, 8(14). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2111.11937.

Schrodinger, E. (1926), Quantisierung als Eigenwertproblem. Ann. Phys., 384: 361-376. https://doi.org/10.1002/andp.19263840404

Shor, P.W. (1994). “Algorithms for quantum computation: Discrete logarithms and factoring”. Proceedings 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science. pp. 124-134. https://doi.org/10.1109/sfcs.1994.365700.

Shor, Peter W. (October 1997). “Polynomial-Time Algorithms for Prime Factorization and Discrete Logarithms on a Quantum Computer”. SIAM Journal on Computing. 26 (5): 1484-1509. https://doi.org/10.1137/S0097539795293172.

M. Steffen, D. P. DiVincenzo, J. M. Chow, T. N. Theis and M. B. Ketchen, “Quantum computing: An IBM perspective,” in IBM Journal of Research and Development, vol. 55, no. 5, pp. 13:1-13:11, Sept.-Oct. 2011, https://doi.org/10.1147/JRD.2011.2165678.

Vandersypen, L., Steffen, M., Breyta, G. et al. Experimental realization of Shor’s quantum factoring algorithm using nuclear magnetic resonance. Nature 414, 883-887 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/414883a

Young Thomas. 1804 I. The Bakerian Lecture. Experiments and calculations relative to physical optics. Phil. Trans. R. Soc.941-16 http://doi.org/10.1098/rstl.1804.0001